It is generally perceived as a land of plenty, full of contented, generous, and somewhat boisterous people, who live life to the fullest. But Punjab has always been a restive place since Independence, and even earlier in the 20th century.

As it zooms back into the headlines with the gangland-style killing of popular singer-turned-politician Sidhu Moosewala and the film 'Udta Punjab' before that, its torturous past needs to be revisited.

Punjab has had a tumultuous history — its wide plains being an easy path for all invaders breaking through the passes of the northwest across the centuries. But if we stick only to the century gone by, it has always been volatile despite the air of calm and contentment.

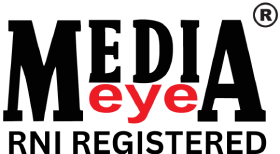

Once regarded as a bastion of British rule, due to the loyal and stalwart soldiers it furnished for the Raj's armies for fighting anywhere in the world — China, Africa, the Middle East, Punjab began changing as the 20th century dawned.

It was then that the fight for India's freedom saw the emergence of a new brand of more direct political action — the troika of 'Lal-Bal-Pal' of whom the first, Lala Lajpat Rai, was based out of Punjab (the other two being Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal).

The Punjabi diaspora — it existed even then, particularly on the West Coast of the US and Canada — was also involved in an armed conspiracy to overthrow the British Raj under the Ghadar Party and fought a clandestine war with British security agencies.

The Jallianwala Bagh carnage and its backdrop is well-known, but in the same decade and the 1920s, so was the struggle, mostly non-violent, to wrest control of leading Sikh shrines, including the Harmandir Sahib, or the Golden Temple, from the mahants who had been "managing" them.

And an example of their management can be seen from the fact that soon after the Amritsar carnage, the then chiefs of the Golden Temple felicitated Brigadier R.E. Dyer, the 'Butcher of Jallianwala Bagh'

It was also this development that led to the formation of the Akali Dal and the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee and their rise over the years to significance in regional politics.

Also, in the 1920s, while Lala Lajpat Rai's death at the hands of police spurred young revolutionaries who believed in armed struggle — and Bhagat SIngh and his friends made the supreme sacrifice for their bravery. Though the 1930s were relatively peaceful, the untimely demise of Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, in 1942, led to the fracturing of the influence of his Unionist Party, which he had co-founded with the Jat leader, Sir Chhotu Ram. Together, they had kept both the Congress and the Muslim League at bay.

Communal friction exacerbated since then on, till the horrors of Partition burst out as India finally gained Independence. There were some hopes that this conflagration, this rampant orgy of unrestrained inhumanity, this dark holocaust, would have a sobering effect on future generations, but it proved to be an illusion.

Sikhs, feeling shortchanged by the Partition, which had robbed them of some of their most productive land and property, as well as key shrines such as Kartarpur Sahib and Panja Sahib, began clamouring for a 'Punjabi Suba', with Master Tara Singh raising the demand right from 1948.

Partitioned East Punjab then, it must be remembered, included what is now Haryana and parts of Himachal Pradesh.

The 'Punjabi Suba' movement, spearheaded by the Akali Dal, encountered resistance from Hindu outfits, who even took out ads in newspapers, ahead of the Census, asking their co-coreligionists to cite Hindi, and not Punjabi, as their mother tongue, and not use Gurmukhi so as to dilute the demand.

For the next decade and half, the movement saw a number of dramatic incidents, including a police raid on and near blockade of the Golden Temple in 1955, mass arrests of the Akalis, and fasts by Tara Singh and his deputy, Sant Fateh Singh. Eventually, the demand conceded in 1966, but the friction during the agitation created a deeping communal rift, whose dire consequences would be seen in the decades to come.

The state also saw a high-profile assassination — of former chief minister Partap Singh Kairon in 1965, but it was found to be a case of personal vendetta, than having political overtones. And while there was peace ostensibly, the Green Revolution and the economic inequities that were unfortunate byproducts of it, and the sectarian divisions the Punjabi Suba demand had created, continued to fester.

The next flashpoint would arise in 1973 with the Akalis passing the Anandpur Sahib Resolution demanding more powers for the states. This would come as the party's Gurnam Singh-led government, which came to power in 1967, saw a turbulent stint with defections and spells of President's rule, and ultimately lost power in 1972.

The resolution would go on to bedevil Centre-State relations for the next two decades, especially when different parties were in power, and fuel the rise of terrorism, as some vested interests seized the issue to seek a Sikh homeland, and charismatic preacher, Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, entered the stage.

It is now mostly forgotten that the ascendancy of Bhindranwale was fuelled by the feud between two tall Congress leaders and chief ministers — Darbara Singh and Giani Zail Singh (later President). One used the fiery preacher to cut down his rival, but in the process created an unpredictable and uncontrollable force. And when Bhindranwale latched on to the Khalistan demand, and the ongoing Sikh-Nirankari tussle, he had become too big to control.

As violence returned to Punjab in the early 1980s, with incidents such as the murder of the Hind Samachar Group's Lala Jagat Narain and Punjab Police DIG A.S. Atwal within the Golden Temple precincts, the radical Sikh groups' threat to disrupt the 1982 Asian Games led to the community being viewed with suspicion by the police and many, including war heroes and other notables, being humiliated.

With Bhindranwale's demands getting more strident, and the growing resentment among the community, the stage was set for what followed — Operation Blue Star in June 1984 to drive out the preacher and his followers ensconced in the Golden Temple, the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the anti-Sikh riots in Delhi and elsewhere, and full-blown insurgency in the state and elsewhere — notably, the assassination of former Indian Army chief A.S. Vaidya in Pune — that took more than a decade to quell.

And yet after peace returned by mid-1990s, the suicide bombing at the Punjab Secretariat in Chandigarh, claiming the life of the then Chief Minister Beant Singh, under whom the last remnants of terrorism were stamped out with the elimination of its top leaders, came as a stark warning that victory also has its price!

Punjab seemed peaceful since the 2000s, but the growing drug addiction problem, attempts to stoke the fires militancy and to pump in arms, the clashes of the Sikh sangat with various offshoots and deras, the incidents of sacrilege, the protests against the farm laws, culminating in the January 26 drama at the Red Fort, and finally, the Moosewala killing, all go to show that trouble and turmoil are always round the corner even the state appears to appears to be calm.